Holding On For Life

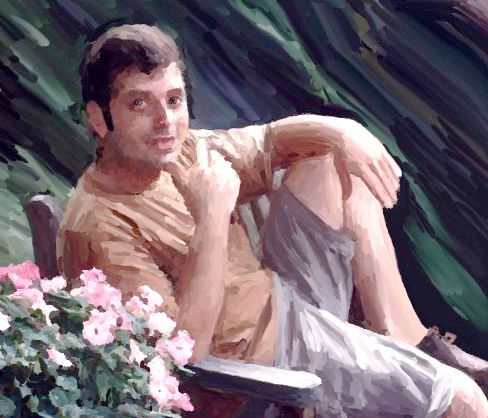

- ᴶⁱᵐ

- Dec 28, 2018

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 28, 2025

Doug was my voice.

He was my heart.

I was his mind.

He was brave and brash.

I figured things out.

I held him when he took his life.

Depression has been a deep dark streak through my family. Each of us has responded to it differently. I've managed — more or less — with medication. My brother Doug, two years my junior, tried that route. The drugs soured and dulled his life, but didn't resolve his depression.

And on the night of his first suicide, when I came into the hospital, he was distraught. Doug was clowned and gowned by a system that controlled him. Usually the bull bursting through doorways, he shuffled. There was no sarcasm. No joking. No anger. No words.

He reached out his hand to mine. I clasped it. Our fingers entwined, my smooth wrist brushing against his newly sutured one. I have never held anyone's hand so closely, so long, so tightly. Neither would let go. The world was that union. If nothing else in the universe made sense, at least that one point of contact did.

When we were young boys, I was voiceless. Speaking to strangers was a baffling skill I was unable to master. Doug was my mouthpiece. If I needed a drink, Doug was there to recognize my need and ask for me. If he wasn't at my side, I would remain thirsty.

When we spoke between us, or in the family, Doug and I would finish each other's sentences. We were connected beyond words.

When we were three and five, we explored the new family house together on moving day — bravely venturing into every room of the daunting three-story building as we held each other, squealing.

On that night in the hospital, holding on, Doug cried to me, lost and frightened. I was — perhaps for the first time — clearly the big brother. I was the lucky one, the one who somehow figured out how to survive, to live, to succeed, to love, to Doug.

I learned a little bit about humans that night. I learned how love felt. I learned how it felt to be needed, to be the last soul left, to be clutched at lest he fall back into the abyss.

What I didn't know, what Doug did, when he finally let go of my hand, was this: he would do it again, better. After his first try, Doug always reserved the right to kill himself. It helped him live, knowing he had a final recourse. When he ultimately took that path, eyes wide open, he took his time, he took his dog, he took his life and he took my love.

It was only after Doug's death I discovered he admired my accomplishments. He knew I struggled to exist in a human world, even if we didn't have the word "autism" to apply to it. Doug was proud of me, though we never discussed it.

I was relieved Doug followed the path he needed. He suffered knowing the pain he would cause. He carefully considered the impact on others and lessened it where he could. In his last moments he held Moocher, already succumbed, close to him. And succeeded. The phrase "rest in peace" was never more apt.

Jim - your writing is a revelation, in all senses of the word. I am only beginning to make my way through your posts but, as I am of a certain age (yours, too, I'd guess), many things, events, ideas, people and understandings are rushing to the fore of my memory. This post and several others I've read are helping me to understand and to process, for lack of a better word, much that has happened in my life and in the lives of others whom I hold close. My own journey into understanding is only beginning and, thankfully, has been blessedly free of tragedy and the kind of trauma so many suffer. That said, what I can take from your writing is already helpful. It is relevant. It is deeply moving. Thank you.

Geeta, I appreciate your support. I am glad you focus on truth, rather than the misguided search for a "cure." All the best to you and your family.

Thankyou Jim to make aware about autism. My elder brother's son and younger sister's son both have Autism and they tried all cure to behave them differently but truth is that they have different strenghts and unique perspectives which we understand now and going to fully support.

I woke up this morning thinking of Douglas. Thanks for this touching glimpse into what was in your brain when he left this earth. It was a devastating time.

I remember being in the hospital with Mom, the day the woman who I counted on to interpret for me had only 2 words firmly in her brain. The reasons I was holding her hand were different, Dad was holding the hand she could feel and she would move to get (very slightly more) comfortable when I wasn’t expecting it. Stroke, when she already knew far too well a body that would not do what she wished. I seem to be holding on this winter, unlike last when I suddenly was told that I had stopped almost everything a few months before. No warning that time, just blankness. Depression is a sneaky thing, and it chose to move from dysthymia to Major Depression by a process I couldn’t see coming that time. Something I couldn’t verbalize after my father got me back to the mental health clinic because it was more a vacuum than an experience. Mom is strong. You are, I am, your brother was. Even mute, or in the hospital. Both in living and in dying.

Your writings touch deeply. We never know who has a silent ailment nor the pain it causes. I am sorry for the loss of Doug nearly 2 decades ago and I am sorry for the loss of your mom last year. I am sure they both, were very proud of you. You are reaching so many with your writing and website! God Bless